Sarah Moore & Dr. Teri Kidd, Animal Protective League

October 6, 2020

Kathy Black, Cat Fanciers’ Association Judge

October 13, 2020

Today’s guest post comes to us from Krista Beucler, Marketing & Communications Intern at Community Cats Podcast.

Kansas State Law 47-624 sounds pretty reasonable. Under the Kansas Statutes for Livestock and Domestic Animals, the law pertains to “any domestic animal affected with any contagious or infectious disease.” These animals are prohibited from being owned by private citizens, kept with other animals, or transported in any way. The intention of the law is mainly applicable to livestock and intends to keep any one animal from spreading disease to a whole herd, especially for animals transported into Kansas from out of state. The law is 30 years old and falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Agriculture. It has been neither enforced well nor updated to reflect recent research.

For cats that test positive for feline leukemia virus (FeLV), the law presents some challenges. When a stray comes into a shelter, if he’s tested for FeLV and the test is positive, the only options the shelter has after the stray hold is up are euthanasia or keeping the cat—but only in isolation from other animals. Since the cat cannot be adopted out, most shelters don’t have the resources to continue caring for FeLV+ cats long term. Cats who have tested positive also can’t be transferred out of the shelter to another state where FeLV+ cats can be adopted. (Kansas is the only state where FeLV+ cats can’t be adopted.) It is even technically illegal to be in possession of an FeLV+ cat, and the law provides for fines of $1,000 for those found in violation. This can, however, be hard to enforce, as an enforcer would need a quarantine order to make an owner get their cat tested.

Another problem with feline leukemia is the common occurrence of false positives in testing. The American Association of Feline Practitioners recommends multiple tests, especially if the first test is positive and the cat is low risk. Because each test costs money, however, shelters are forced to decide whether to spend precious resources on multiple tests, with the chance that they will still have to euthanize, or to not test at all, and potentially be in violation of the law by adopting positive cats to uninformed adopters.

Though research is still being done, studies are finding that the risk of FeLV transmission is lower than originally thought. It is most commonly passed by an infected mother to her kittens through her milk. It can be passed through bite wounds, but with successful management of colonies through TNR, aggressive behaviors like fighting become less common. Among fixed cats, transmission is uncommon unless the cats are a bonded pair that spend a lot of time grooming each other, though more research is necessary about how the virus spreads in the home. In a shelter setting, it is still a good idea to keep FeLV+ cats in their own kennel or their own room, and group-housed cats should all be tested. Because the virus is fairly fragile in the environment, as long as a kennel or cage is cleaned well after housing an FeLV+ cat, there should be little risk of transmission for the next cat placed in the kennel.

According to the 2020 American Association of Feline Practicioners (AAFP) Feline Retrovirus Guidelines, “In response to goals to save all healthy and treatable cats, a growing number of shelters have expanded their adoption programs to include cats with FeLV and FIV infections. These cats should be held in single-cat housing or group accommodations that segregate them from uninfected cats pending adoption. There are no medical reasons to exclude retrovirus-infected cats from public adoption rooms in shelters, offsite adoption events, or satellite adoption centers such as those at pet stores if they are housed separately and properly documented. Similarly, legislation in the USA aimed at excluding retrovirus-infected cats from shelter adoption and interstate transport programs is not supported by current medical evidence.” The Guidelines go on to say, “Since stress can exacerbate the clinical course of both FeLV and FIV infection, adoption into a home-like setting is likely to result in better long-term outcomes.”

According to the 2020 American Association of Feline Practicioners (AAFP) Feline Retrovirus Guidelines, “In response to goals to save all healthy and treatable cats, a growing number of shelters have expanded their adoption programs to include cats with FeLV and FIV infections. These cats should be held in single-cat housing or group accommodations that segregate them from uninfected cats pending adoption. There are no medical reasons to exclude retrovirus-infected cats from public adoption rooms in shelters, offsite adoption events, or satellite adoption centers such as those at pet stores if they are housed separately and properly documented. Similarly, legislation in the USA aimed at excluding retrovirus-infected cats from shelter adoption and interstate transport programs is not supported by current medical evidence.” The Guidelines go on to say, “Since stress can exacerbate the clinical course of both FeLV and FIV infection, adoption into a home-like setting is likely to result in better long-term outcomes.”

There is an FeLV vaccine, and though it is not 100% effective, some studies have shown an immunity of 12 months to 2 years in vaccinated cats. The 2020 AAFP guidelines recommend that all kittens up to 1-year-old, all outdoor or indoor/outdoor adult cats, and all cats living with an FeLV+ cat get vaccinated.

Advocates in Kansas have been working on trying to update the laws to reflect current research. Legislators are particularly worried about livestock and how infectious diseases can affect herds, so they hesitate to change the wording of the law, even though the implications of the law for pets are different than for livestock. Under the Pet Animal Act, an exception (K.A.R. 9-18-23) was recently made for FIV+ cats, allowing them to be transported and adopted, so advocates are hopeful that the regulation can be extended to apply to FeLV+ cats as well.

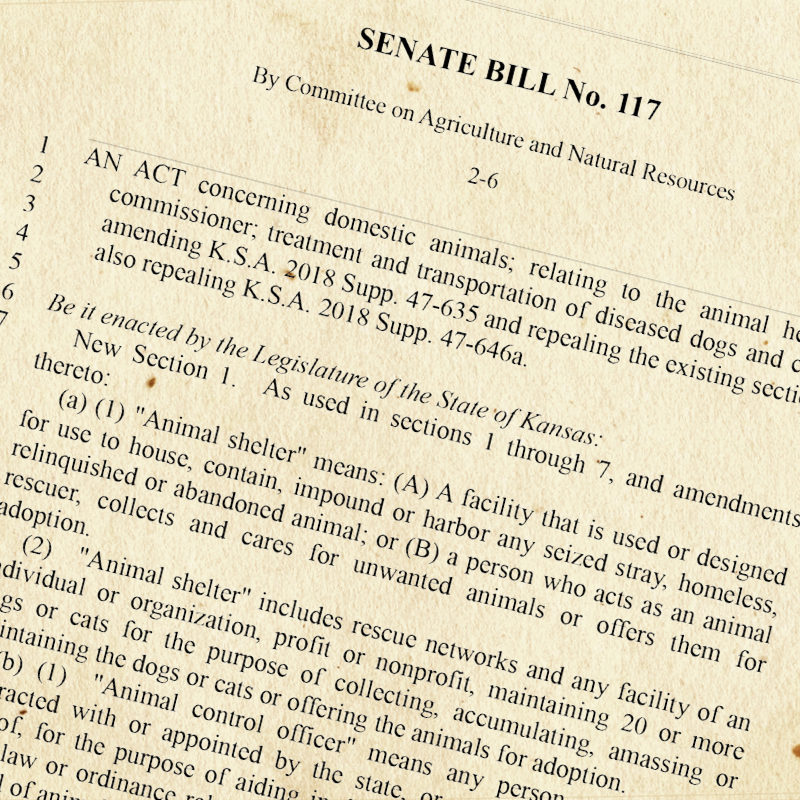

Midge Grinstead of the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) has been working as an animal advocate to update the laws in Kansas. She worked for nine years to change the Pet Animal Act, and she has provided legislators with current research on FeLV and the recommendation of adoption for FeLV+ cats. She entered testimony in favor of a bill last year (Senate Bill 117) that would allow for domestic animals to be adopted and transferred despite an infectious disease at the recommendation of a veterinarian. Unfortunately, the bill died in committee and never made it to the floor of the Kansas State Legislature.

Now that the Legislature is in recess, Midge hopes to mobilize shelters in Kansas to call their representatives to bring attention to this issue. Though there is still much we don’t know about FeLV, more and more credible research is becoming available every day. The laws that govern the fates of cats that test positive for FeLV must change to reflect this research and to support the recommendations for best outcomes for infected cats.

Originally from Colorado, Krista Beucler received a Bachelor of Arts in creative writing at the University of Mary Washington (UMW) in Virginia. She was the editor-in-chief for Issue 7.2 of the Rappahannock Review, the literary journal published by UMW. Krista is a winner of the Julia Peterkin award, and her creative work has been published in From Whispers To Roars and South 85 Journal and is forthcoming from Under the Sun magazine. She is spending COVID-19 at home with her cats.

Originally from Colorado, Krista Beucler received a Bachelor of Arts in creative writing at the University of Mary Washington (UMW) in Virginia. She was the editor-in-chief for Issue 7.2 of the Rappahannock Review, the literary journal published by UMW. Krista is a winner of the Julia Peterkin award, and her creative work has been published in From Whispers To Roars and South 85 Journal and is forthcoming from Under the Sun magazine. She is spending COVID-19 at home with her cats.